At the end of February, Kayla Rae Whitaker returned to Appalachian to give a craft talk and a lecture as part of the ongoing Visiting Writers Series. Her craft talk was to an engaged group about the value of getting an MFA in creative writing. Whitaker herself received her MFA from New York University and has published her own novel The Animators. Whitaker recounted her own journey to publication, discussing how she first used her undergraduate degree and her first post-college job to dedicate time to writing and reading before applying to New York University. She talked about allocating from her own free time for her creative work and said that the key was to always be writing.

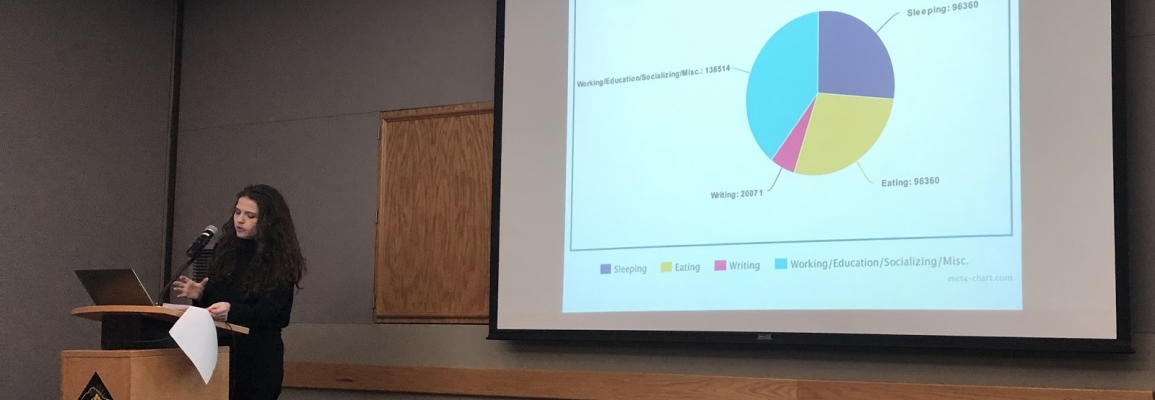

Later the same day, Whitaker gave an inspiring craft talk titled "Five Things You Need to Do Before You Publish" that served as a guidebook for positive actions to take before you approach a publishing agent. During the talk Whitaker stressed mindfulness, literary citizenship, collaboration, and the importance of learning how to embrace rejection. The latter is perhaps what stuck out the most, as she began by answering the common question of "Why You?" essentially why she, in particular, got published. The short answer? Constant hard work and dedication - and then she broke down how she invested 20,071 hours into her writing.

Whitaker described how she committed to daily writing practices, scheduling time each day to just sit down and write, and also to getting sober. She stated, "During my initial sobriety I found myself perpetually at a loss, but when I sat down to write I knew exactly what to do; I was compelled, I was inspired, I was intellectually engaged." She also pointed out that sobriety and writing both deal with control, as you do not have much control in life; you must grasp at control where possible and learn to accept the uncontrollable where it is not. Whitaker asserts that authors have very little control over the biases and tastes of their readers, and that "the sole factor over which you do have control is your process" so you must organize it, perfect it, and make sure that your process and writing is both productive and meaningful.

This importance of grabbing the reins of control that you're able to further punctuates Whitaker's views regarding rejection and failure. The dedication to the writing process must not be hindered by dismissal. Whitaker states that "rejection is a universal hurt" from which no one is immune, particularly writers and artists who experience rejection constantly. The more comfortable you are with rejection and failure, the more prepared you are to learn through "botched execution," the more mindful and better writer you'll become.

If you're realistic you will walk into this life knowing that getting told no is a constant unceasing given, and that it's not a reason to quite writing, it's a reason to find the best possible reasons for writing, and those reasons may or may not include publishing

Whitaker emphasizes that normalizing failure is important and can be accomplished via the integrity of the workshop space, or through action tactics like taking a constructive inventory of your own work and identifying your most systemic problems. The ability to adapt to failure, and change, is essential in writing, as "the creative process is an exercise in fluctuation" and "making art is an exercise in living and operating with a sense of humility." Immersing yourself in your work while writing the drafts is important, but being able to fluctuate and distance yourself to a more objective outlook of an editor is equally vital. Workshops can be incredibly helpful to the creative and editing processes, and the community and readership gained from that collaboration are just as valuable.

Kayla Rae Whitaker concluded her craft talk with some tidbits of advice: surround yourself with a supportive community of readers and writers, feed your creativity with a healthy diet of prose, learn to work under the weight of the word no, and most importantly: "don't play fast and loose with your hours; hours are all we have."

Written by Jules Millward and Daniel Mosakewicz

Photos by Jules Millward